Updates

On January 19, 2016, we received a letter from the U.S. Department of Energy notifying us that our proposal was not selected.

Notification letter (287 KB PDF)

On March 3, 2016, we received merit review comments from DOE.

Merit review comments (65 KB PDF)

A significantly reworked version of the Decentralized Solar Decathlon concept is being developed as the Global EcoHouse Competition (GEHC).

Background

The Consortium for a Decentralized Solar Decathlon (CDSD) is an unincorporated consortium of former Solar Decathletes and Solar Decathlon faculty advisors led by Live to Zero LLC. We have submitted a proposal for the Department of Energy’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) funding opportunity announcement DE-FOA-0001371 (“Solar Decathlon Program Administrator”).

Our proposal responds directly to the following challenge presented in the FOA:

“These [FOA] requirements for the venue are based on DOE’s experience with Solar Decathlon competitions since 2002. DOE welcomes new ideas and/or alternatives that may produce a better or more impactful event.”

Considering the program’s unprecedented budget constraints (summarized below) and EERE’s stated goal of producing a “better or more impactful event,” CDSD has concluded that decentralization is the only viable option.

The FOA specifies the following key funding and budget provisions:

- $3-4 million in federal funding from EERE over the next four years ($1.5-$2 million for SD2017 and $1.5-$2 million for SD2019)

- $4 million in prize money distributed to the teams over the next four years ($2 million for SD2017 and $2 million for SD2019)

- Minimum 50% cost share percentage by the new Program Administrator and its sponsors/partners.

Assuming $8 million in total required budget over the next four years ($4 million for administration + $4 million for prize money), CDSD must raise $4-5 million from sponsors (mostly cash, some in-kind) to meet the 50% cost sharing threshold.

According to data published in a publically-available EERE BTO Program Peer Review presentation, a traditional, centralized Solar Decathlon costs about $20 million over four years ($16 million for administration + $4 million for prize money). After the $4 million federal funds contribution, $16 million in sponsorships (or 80% cost share) would be required.

Mission

The Consortium for a Decentralized Solar Decathlon will substantially increase the depth and breadth of the Solar Decathlon program’s impact by hosting the competition in 20 campus communities across the country. Decentralization will also restore the program’s long-term fiscal sustainability and growth potential by reducing administrative costs by 75% and creating exciting new sponsorship opportunities.

Key Proposal Contents

We encourage you to advocate for Solar Decathlon decentralization. Feel free to use the follow elements of our proposal in your advocacy efforts:

Calls to Action

To support the decentralized Solar Decathlon concept, please take one of the following actions.

Browse the key proposal contents and take one of the following actions.

- If you have a few seconds, send a quick email to decentralizedsolardecathlon@livetozero.com in which you state your support for decentralization. If you don’t support this concept, we’d like to know that too because we do not want to advocate a concept that is unpopular within the extended Solar Decathlon community.

- If you have a few minutes, send a PDF letter of support to decentralizedsolardecathlon@livetozero.com in which you justify your opinion that Solar Decathlon should be decentralized.

- If you have an hour, think of some ways in which you could contribute to the decentralized Solar Decathlon if it moves forward and send a letter of intent or a letter of commitment to decentralizedsolardecathlon@livetozero.com. Some ideas for future contributions follow:

- Identify potential sponsors from your professional network (DOE will require 50% cost sharing from its new Solar Decathlon Program Administrator).

- Serve on a Solar Decathlon Board of Advisors that would help us and the teams solve new logistical challenges associated with building permanent houses on campuses, help us refine contest criteria and the rules, help new teams navigate the project, and help new teams navigate the project’s challenges.

- Nominate outstanding students, graduates, and colleagues (or yourself!) for volunteer, intern, and/or permanent positions with the Solar Decathlon program.

- Submit a proposal to compete in a future Solar Decathlon and/or encourage colleagues from other schools to submit proposals.

- Volunteer as a contest juror and/or nominate potential jurors from your professional network.

- Invite us to include your past SD house(s) in a small, decentralized, pilot Solar Decathlon competition in early-2016.

- Use your past SD house(s) for education, workforce development, and/or research activities and tell us about your successes and challenges.

Please contact us at decentralizedsolardecathlon@livetozero.com if, after browsing the key proposal contents, you agree with us that decentralization is best path forward for Solar Decathlon. We welcome additional partners.

If the CDSD proposal is selected, we plan to hire the following subcontractors:

- PR/Marketing Manager

- Sponsorship Coordinator

- Web Developer

- 3D Visualization Artist

- Blogger/Writer

- Graphic Designer.

Our objective is to create a team consisting entirely of Solar Decathlon alumni and other individuals/companies within the extended Solar Decathlon community. Please contact us at decentralizedsolardecathlon@livetozero.com if you are interested in working with us.

Please review the draft sponsorship program in the “Sponsors” tab below. Contact us at decentralizedsolardecathlon@livetozero.com if you are interested in having an initial conversation about sponsoring the decentralized Solar Decathlon.

Feedback

The following Solar Decathlon teams and faculty leaders have responded to requests for comment regarding decentralization.

(* anonymous team response)

Mona Azarbayjani (SD13 North Carolina)

Stuart Baur (SD07 Missouri S&T)

Vincent Blouin (SD15 Clemson)

Martha Bohm (SD15 U at Buffalo)

Mike Brandemuehl (SD02/05/07 Colorado)

Jeffrey Brownson (SD09 Penn State)

Ralph Bruce (SD15 Team Tennessee)

Estefania Caamaño (SD05 Madrid)

Pliny Fisk (SD07 Texas A&M)

Amy Gardner (SD07/11 Maryland)

Richard Garber (SD11 Team New Jersey)

Geoff Gjerston (SD09 Louisiana)

Julee Herdt (SD02/05 Colorado)

Andrea Kertz-Murray (SD09/11 Middlebury)

Johann Kyser (SD11 Canada)

Steve Lee (SD02/05/07 Carnegie Mellon)

Ed May (SD15 Stevens)

Mark McGinley (SD13 Kentucky/Indiana)

Ty Morrison (SD19 Boise State)

Marilys Nepomechie (SD11 Florida Int’l)

Derek Ouyang (SD13 Stanford)

Ulrike Passe (SD09 Iowa State)

David Peronnet (SD13 Tidewater Virginia)

Heath Pickerill (SD13/15 Missouri S&T)

Joe Richardson (SD15 Team NY Alfred)

David Riley (SD07 Penn State)

Clarke Snell (SD15 Stevens)

* Cal Poly (SD05/15)

* Stevens (SD15)

Mark Taylor (SD09 Illinois)

* Team Tennessee (SD15)

* Texas/Germany (SD15)

Christian Volkmann (SD11 Team New York)

Mark Walter (SD09/11 Ohio State)

Bill Hutzel (SD11 Purdue)

* Sacramento State (SD15)

* Team Orange County (SD15)

General Information and Key Proposal Excerpts

In the decentralized Solar Decathlon, twenty collegiate teams design, build, operate, and present permanent zero energy homes on their respective campuses.

The following chronological list of project phases and milestones describes the proposed high-level operational details of the decentralized competition:

- During the design development phase, the program administrator publishes the Rules document and prepares for the construction and competition phases while the teams work on the design and documentation of their homes.

- During the construction phase, student team members install competition instruments in the houses under the direction and oversight of competition management.

- In late summer, competition management performs onsite inspections and makes baseline performance measurements. Also in late summer, Architecture and Engineering contest juries conduct remote evaluations of the houses using live video and virtual 3-D tour technologies.

- In early fall, the yearlong competition phase kicks off with six weekends of team-led public events in the twenty selected campus communities across the lower 48 U.S. states. The public events occur during these communities’ peak weekends, when student move-ins, homecoming celebrations, tailgating parties, football games, cultural events (including the National Tour of Solar Homes), and the best weather of the year attract numerous visitors from around the region.

- Five contiguous days of Indoor Environment and Energy Balance contest monitoring are conducted every other week during the competition phase. During non-monitored weeks, volunteer occupant groups live in the houses and participate in “post-occupancy evaluations,” which contribute to the houses’ Livability contest scores.

- During late fall, winter, and early spring of the competition phase, the teams focus on their respective Research & Development (R&D) contest projects, host small weekend events and tours at the house, and produce educational programs and material for the local community’s K-12 students, homeowners, and other stakeholders.

- As the weather warms up, the teams host two weekends of public events at their houses to celebrate the arrival of spring, the end of the school year, and the homestretch of the competition phase.

- Each team’s core group of students and faculty remain on campus during the summer to write final reports that summarize the teams’ research, development, and education projects and results.

- In late-summer, the R&D and Education contest juries review the teams’ final reports and attend online presentations given by the student team members.

- The competition phase concludes as the fall semester begins and visitors return in large numbers to the twenty campus communities. One of the weekends of public events at the houses coincides with the U.S. Department of Energy’s awards ceremony and media event in Washington, D.C. A constituent from each of the twenty teams is invited to attend the event, where a live video feed of the teams at their house sites accompanies the announcement of the competition’s top three finishers. The event is streamed live on “Solar Decathlon TV” for the general public and non-attending team members.

- By the time the awards ceremony has occurred, the teams for the next Solar Decathlon have been selected and are deep into design development.

.

| Contest | Points | Brief Description |

| Design | 100 | A jury of experts evaluates the following design elements of each project: architecture, interior design, lighting, landscape architecture, water conservation, health and safety, and building life cycle. |

| Livability | 100 | Similar to previous “Market Appeal” contests, but post-occupancy evaluation (PoE) data are also considered by a jury of experts |

| Affordability | 100 | Similar to previous Affordability contests |

| R&D | 100 | Teams design and execute one or more R&D projects and publish results, which are evaluated by a jury of experts |

| Education | 100 | Teams design and execute one or more education projects and publish results, which are evaluated by a jury of experts |

| Outreach | 100 | Teams design and implement strategies that maximize the number of individuals impacted by the project and the quality of those individuals’ experiences; results are evaluated by a jury of experts |

| Comfort | 100 | Similar to previous “Comfort Zone” contests, but the evaluation is broader in scope and more rigorous in execution, as required by a yearlong competition in diverse climates. |

| Energy Efficiency | 100 | Conceptually similar to a HERS rating or Home Energy Score, but PV production is disregarded |

| Energy Balance | 100 | Similar to previous “Energy Balance” contests, with PV production included |

| Smart Grid | 100 | Evaluates the following elements: demand control (including plug-in vehicle integration), occupant awareness, occupant control, and grid autonomy |

| TOTAL POINTS | 1000 |

Intended Outcome #1: Greater Educational Impact

- Increase the quality and average duration of each physical and virtual house visit.

- Increase the total number of physical and virtual house visits by the general public, college students, and K-12 students during the competition.

- Increase the volume of high-quality, widely-available educational materials produced by the teams and disseminated by the administrators.

Intended Outcome #2: Greater Workforce Development Impact

- Increase the number of student team members who enter the STEM education field.

- Increase the percentage of student team leaders who work in the building sector after the competition.

- Increase the number of EERE-related companies started by student team members after the competition.

Intended Outcome #3: Greater R&D Impact

- Increase the number and quality of Solar Decathlon-related academic papers and presentations made by participating students and faculty.

- Increase the participation of Solar Decathlon teams in Building America and other federal/state/local government-sponsored EERE programs.

- Increase the number of Solar Decathlon-related patents that are filed within 3 years of the competition evaluation period.

Intended Outcome #4: Greater Market Transformation Impact

- Increase the number of new and/or retrofit residential projects within 20 miles of each participating campus that adopt significant design or physical elements of Solar Decathlon houses.

- Increase the number of homeowners within 20 miles of each participating campus who hire building energy auditors and energy efficiency experts within 1 year of the start of the competition evaluation period.

- Increase the number of media impressions per competition.

Intended Outcome #5: Fewer Adverse Environmental Impacts

- Reduce the emissions attributable to construction, assembly, transportation, team travel, and house visitation travel.

- Reduce the quantity of houses and constituent components that are moved, abandoned, neglected, unused, or discarded during first 12 months after completion of construction.

Other Performance Objectives

- Increase the number of SD2021 team proposals, as compared to SD2015 proposals

- Increase the rate of Solar Decathlon “franchising” by states, regions, and the international community by the end of SD2019.

- Reduce (in real dollars) the size of the prize purse for SD2021, compared to SD2017

- Reduce (in real dollars) the federal funds contribution for SD2021/2023, compared to SD2017/2019.

- Long-term “reach” goal: At least one prototype zero energy home on each of the Power Five conference schools’ campuses by the end of SD2025.

Decentralization removes many of the technical and logistical constraints that severely limited the teams’ design options in the past. A list of new design options follows:

- Climate- and market-responsive designs

- Significantly larger houses

- Permanent foundations

- Diverse geometries

- Multi-level houses

- Diverse construction methods

- High-mass thermal storage strategies

- Site integration.

The yearlong competition introduces the following new opportunities that were impossible or impractical in a 9-day competition:

- Rigorous yearlong performance evaluation under monitored conditions

- Periods of occupancy by members of target market

- Long-term R&D projects

- Long-term education projects

- Long-term outreach strategies.

CDSD believes that every Solar Decathlon team should be required to answer the following high-level research questions by the conclusion of the completion:

- What is the measured yearlong energy balance under typical conditions? Is the measured energy balance within 10% of the predicted energy balance? If not, why not?

- Which elements of the design perform as intended? Which of the most innovative elements have good market potential? Justification your claims and present preliminary commercialization plans.

- Which elements of the design do not perform as intended? Why do they not perform as intended? How can they be modified in future projects so they perform as intended?

- What is the local community’s response to the Solar Decathlon program? What is the local community’s response to the team and its design? Be specific. Collect and present survey, interview, and anecdotal data.

These questions were mostly unanswered during the ’02-’15 Solar Decathlons because of the brief competition period, the budget pressure imposed by the centralized model, and the house characteristics imposed by the centralized model. The reduced administration and team costs; design flexibility; yearlong evaluation; new Livability, R&D, Education, Outreach, Energy Efficiency contests; improved Comfort and Energy Balance contests; and centralized CMS proposed herein virtually guarantee that all the above research questions will be answered by every Solar Decathlon team and all the results will be disseminated for widespread use via the Solar Decathlon website.

The following shorthand notes outline decentralization’s numerous benefits.

- Administration costs. Decentralization is the only viable concept for accommodating DOE’s reduced project budget. Our proposal is the least risky because we are intimately familiar with the project’s unique challeges and we will not feel pressure to overpromise and under-deliver to meet the budget targets. We also do not face the nearly impossible challenge of attracting unprecedented levels of sponsor funding with an event that has arguably been declining in popularity since the move from the National Mall after 2011.

- Sponsor opportunities. More relevant target market↔sponsor relationship/connection. Direct exposure to entire campus, instead of <1% of student population.

- Student interest and engagement. Higher quantity/better quality student involvement. No more “missing the cut” to join the core team at the competition site. Permanent campus facility for future students to use for projects/theses/dissertations. Visible/touchable opportunities for improvement motivate participation in future competitions and increased likelihood of campus “solar villages.”

- Cost of entry and participation. Lower cost of entry and better ROI for schools leads to more applications and better projects. Better opportunities for prospective team sponsors because of increased exposure to and contact with target market. In the past, it was very difficult to find a house transportation/assembly/disassembly/travel/lodging sponsor because of the disconnect between the team’s needs and potential sponsor’s needs. No house transportation/assembly/disassembly cost, much less team travel/lodging cost, etc.

- Environmental impact. No house transportation, much less team member travel, much less site visitor travel.

- Educational, workforce development, R&D, and market transformation impact. Permanent houses in high-traffic locations with diverse audiences over many years creates an environment for people to have valuable and unexpected interactions with the project. This leads to impactful results and opens up future possibilities.

- Future potential, exciting possibilities. Over the past 2 years, DOE has challenged the community to propose significant, impactful changes to the program that would address increasing budget pressure and declining popularity of the program within and outside of Washington, D.C. Decentralization and its increased use of technology, new storylines, reduced risk, and greater ROI for all stakeholders is the concept that meets DOE’s challenge.

- New audiences. Investments in new audiences, such as local communities, educators, students, academics, and the uninformed sector of the general public are possible because administrative cost reductions offer the budget flexibility required for to make these investments. Obviously, the National Mall was a very unique centralized competition site, primarily because visitors come to DC to learn and policy-makers reside in DC. No other city offers these benefits. College campuses come the closest.

- Rewarding the right teams for the right reasons. The quality of the evaluation will be invulnerable to unanticipated circumstances, such as weather systems, power outages, broken truck axles, etc. This is more important than ever before because of the new tiered prize purse model. The pressure on DOE and its program administrator to conduct a fair, compelling competition with rock-solid results will be unprecedented because the stakes are so much higher.

- Content opportunities. More diverse and interesting photo, video, media, educational, research, feature story, profile, and other content opportunities. The depth, breadth, and quality of printed and online content has inevitably declined in recent years because of general defunding and budget pressures imposed by central site administration requirements.

- Climate-responsive designs. All buildings, and especially educational/research prototypes, should be designed for the climate in which they are designed to operate during their complete lifecycle. Designing a building for two climates and then evaluating the building in very mild conditions in the less-representative climate is and always has been one of the most problematic elements of the centralized competition. The direct and indirect consequences of this logical disconnect are serious. The decentralized competition immediately puts this issue to rest and opens up numerous new possibilities for the houses that were previously unavailable.

- Market-responsive designs. See the discussion in the above item. A similar logical disconnect also exists when a building is designed for a particular target market, but is not located, experienced, and evaluated within that target market.

- Competition more relevant and relatable; no more “abstraction of reality” explanation. Larger houses, permanent foundations, site integration, realistic design/build process, and a yearlong evaluation mean that competition stakeholders no longer have to respond to the competition’s critics on the basis of the competition being “an abstraction of reality” or merely a “demonstration.” By transitioning the competition from “abstraction of reality” to “reality,” the project will gain respect from a range of new stakeholders, such as sponsors, the Building America Program, PV installer training organizations, university researchers, the general public, the academic community, etc.

- Onsite/online visitor experience. No more waiting in line or navigating a large crowd in a small space to truly experience all the houses. New technologies and a flexible budget expand the possibilities for the competition to reach more people in new ways. Today’s 3D Virtual Reality options, such as those offered by Matterport, are more affordable, fun, and realistic than ever before. By SD2019, they will be even more affordable, fun, and realistic. By embracing these technologies, the SD2017 and SD2019 Solar Decathlon houses will be experienced by exponentially more people than all the previous competitions’ houses combined. These technologies make the expansion of the competition’s impact in the K-12 education community particularly exciting.

- Growth opportunities. The dramatically lower cost of entry, increased ease of execution, and higher ROI mean that many individual states, individual climate regions, and additional countries will become Solar Decathlon “franchisees.” Thus, the program’s impact will expand horizontally at no additional cost to DOE.

- No academic compromises. Many fewer missed classes, academic calendar issues, engineers/architects working in unrelated disciplines (e.g., house transportation), etc.

- Team expenses with long-term ROI. In the decentralized model, teams can easily justify all project expenses to the university and the team’s potential sponsors because the ROI are compelling and immediately apparent. Fewer necessary expenses will have little/no sponsorship potential or ROI, such as house/team transport.

- Rental income opportunities. Teams have new opportunities to recoup costs by renting houses to students, to other campus entities, or to outside groups.

- Permanent campus facility. The likelihood these permanent buildings will be sold or otherwise disposed of after the competition, and never to be seen again, dramatically decreases. Because the buildings are permanent, larger, better proportioned, and better integrated into the site, the university will consider the buildings as permanent campus assets, will maintain them accordingly, and will maximize their long-term value to the campus community.

- High-impact event. The final awards ceremony can move back to Washington, D.C., where it belongs for many obvious reasons.

- Agility. The elimination of the program administrator’s Event Production and Site Operations sub-teams means that a more agile and efficient workflow can be adopted, and the program administrator can be more responsive to impromptu DOE requests.

- Competition-to-competition improvements. A full year of performance data in 20 competition houses will be extremely valuable to subsequent competition teams and the building science community, which is always starving for high quality performance data. The new feedback cycles that the 365-day evaluation makes possible will result in larger incremental project improvements from one competition to the next.

Target Audiences

- K-12 students

- STEM educators

- Current and prospective college students

- Building and renewable energy scientists and researchers

- Current and prospective homeowners

- Homebuilders, contractors, and realtors

- Parents of college students

- Tourists.

Sponsorship Levels

| Level | Value (Cash + In-Kind) Per Competition | Benefit |

| Presenting Sponsor | $1,000,000 |

|

| Contest Sponsors | $100,000 |

|

| Supporting Sponsor | <$100,000 |

|

How are houses evaluated against each other if they are operated in different climates?

The performance evaluation of one house against another is not climate-dependent, as demonstrated by Live to Zero in the decentralized Oman EcoHouse Design Competition. In fact, a higher quality competition is much more likely if the houses are operated and evaluated in the annual climates for which they were designed.

Is it appropriate for the Design jury to evaluate the houses remotely?

The vast majority of evaluations for reputable architecture and engineering design competitions are done remotely. Video and virtual reality technologies make this more appropriate and affordable than ever.

Are the SD2017 teams being selected on the basis of their ability to build a mobile home that can be easily assembled and disassembled multiple times and transported across the country?

House mobility and transport is not explicitly mentioned as requirements or criteria of the team selection solicitation document. Furthermore, although the document states that the SD2015 Rules will be the basis for the SD2017 competition and it implies that the competition will be centralized, it also states that the Rules will be revised for SD2017 and that all teams are encouraged to “identify a permanent location for the house following the competition.” Clearly, the document does not preclude a decentralized competition. However, it may be advisable to disqualify teams that have not identified a suitable permanent site and either host a competition with fewer than 20 teams or replace those teams via a new solicitation.

Assuming a typical 1- to 2-year design/build process and a 1-year competition evaluation period, how can the program maintain a 2-year project cycle?

The decentralized competition administration phases and workflow are designed to easily accommodate this overlap. The teams for the next competition will be selected and begin design during the current competition’s competition phase.

Will the physical Solar Decathlon village's sense of community and camaraderie among the teams be lost with decentralization?

Although the final event in Washington, DC and the increased opportunities for online interactions will partially compensate for this loss, CDSD has not yet come up with a way to fully compensate for this loss. This is, admittedly, the biggest weakness of the decentralized concept.

One potentially compelling idea is to establish a Decathlete exchange program in which a contingent of students from one team live in another team’s house for a period of time. We have also started to develop some ideas for inter-team collaboration during open house weekends.

Additional ideas are welcome!

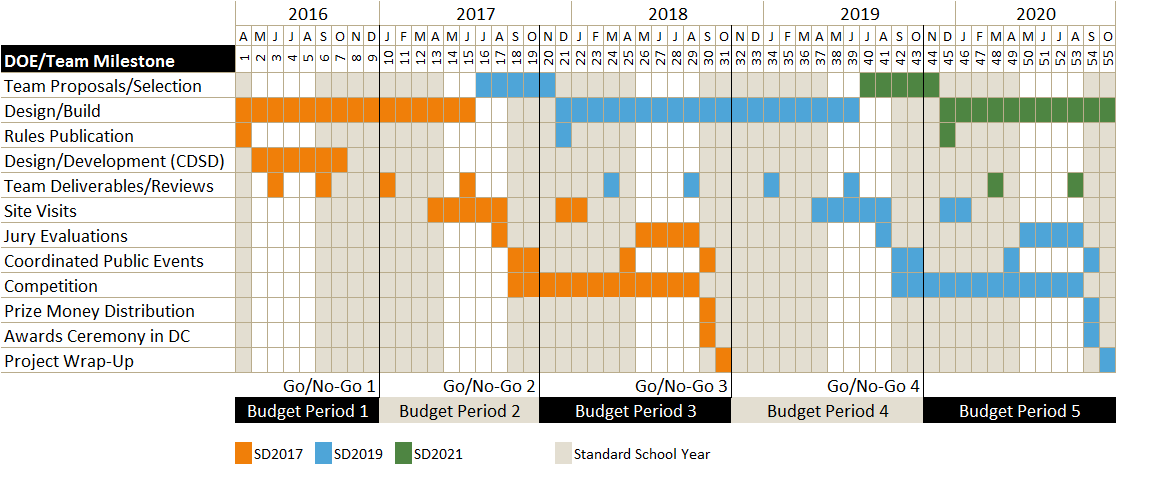

Draft Schedule